Friday, February 26, 2010

A message from the biographiographer ...

A whoreson tisick, a whoreson rascally tisick so troubles me … and what one thing, what another … and I have a rheum in mine eyes too, and such an ache in my bones that, unless a man were cursed, I cannot tell what to think on the blog. Normal (?) service will be resumed as soon as possible.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

The loss-making landlord, the impoverished playwright, the famous left foot and a grim left footer.

George Brooke inherited 6,500 acres in Kildare and Wicklow as well as a stake in the family wine business of which he was the nominal head (others did the actual work). Upon returning to Ireland from Cambridge (no degree), he rode to hounds and became an enthusiast for evicting his tenants. In two weeks in July 1887, he turfed out more than 70 families. Later, he spent £20,000 trying to install "suitable" (i.e., non-militant) tenants to replace those who had been evicted. Upon the failure of this effort, he declared victory and wore down the government in his efforts to obtain a baronetcy: it succumbed and elevated him in 1903. The title survives, as attested by this self-parodying entry at a website called thepeerage.com:

George Bernard Shaw, an Irishman, famously wrote (in his preface to Pygmalion) that it is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him. The Irish shouldn't be so smug. A few years ago, my solicitor in Dublin committed suicide when he was about to be exposed for serious financial irregularities. One of the national newspapers, not even attempting to hide its its schadenfreude, wrote that he "seemed to be the epitome of protestant respectability". Do I note similar slippage in the DIB's entry on John Brougham the actor-playwright: "born ... in what appears to have been a respectable protestant family"? Let it pass: Brougham (pictured) is more interesting. A rival of Dion Boucicault, he claimed to have co-written one his his hit plays, London Assurance, although he lost a lawsuit pressing his claim. Like Boucicault, he had hits in Dublin, London and New York, and was a prolific writer, responsible for more than 160 plays and other stage works. He performed oratory by Daniel O'Connell and the temperance campaigner Father Mathew, dramatized popular novels such as David Copperfield and created hit burlesques. The DIB believes that in one burlesque, PO-CO-HON-TAS, this southern anthem Dixie was "introduced" but I believe it predated the show by a couple of years. Regardless, PO-CO-HON-TAS was a big and long-running hit: it even opened Dublin's Gaiety Theatre, still standing, in 1872. His personal life was less complicated than Boucicault's, although he is described as being "[g]enerous, extravagant, and improvident, and noted for helping others get rich while he got poorer."

We're probably all familiar with the story of Christy Brown, from his memoir My Left Foot and Jim Sheridan's film of the same title with Daniel Day-Lewis. It's worth recalling though: one of 22 children of a Dublin bricklayer, of which 13 survived, he was paralyzed from birth, except for the use of the famous foot. He began using it to write with chalk, then started painting at the age of 10. His memoir, published when he was 22, was followed by novels and poetry and his painting were widely exhibited. Not surprisingly, he could be "moodily cantankerous and obstinate", although he could also be "witty and gregarious".

I've mentioned before that the cutoff date for the DIB is 2002, by which you have to be dead to be considered for inclusion. This generally means that you have to be antique, but still leaves room for a few who died before their time. Thus we have a contemporary figure, Jimmy Brown, "republican socialist and drug-dealer". The Northern Ireland Troubles through up a toxic mixture of guerrillas, politicos, gangsters and psychopaths, sometimes all incarnated in the same person. Brown's breakaway Irish Republican Socialist Party and its military wing, the Irish National Liberation Army, engaged fully in killing unionists, as well as those nominally on its own side who had committed ideological or other crimes. They took up drug dealing to raise money for arms, and had the bright idea of recruiting people who knew how to deal drugs, i.e. criminals. This of course caused them huge problems in the communities were the drugs were dealt, notably their own. Certain loyalists did the same thing, and the war of national liberation descended into something much uglier: a gangsters' turf war. Jimmy Brown was finally liquidated by the IRA, which had lost patience with the various splinter groups. The DIB's Patrick Maume writes well that he was a "devious man who deceived himself [and] provided an ideological veneer for sectarian murder and criminality". Ugly times.

Sir Francis George Windham Brooke, 4th Bt. was born on 15 October 1963. He is the son of Major Sir George Francis Cecil Brooke, 3rd Bt. and Lady Melissa Eva Caroline Wyndham-Quin. He married Hon. Katharine Elizabeth Hussey, daughter of Marmaduke James Hussey, Baron Hussey of North Bradley and Lady Susan Katherine Waldegrave, on 8 April 1989. Sir Francis George Windham Brooke, 4th Bt. was educated at Eton College, Eton, Berkshire, England. He succeeded to the title of 4th Baronet Brooke, of Summerton, Co. Dublin [U.K., 1903] in 1982.(I've just realized who the father-in-law is: "Duke" Hussey, the newspaper executive and chairman of the BBC. I've actually read his autobiography. Strictly for professional reasons.)

George Bernard Shaw, an Irishman, famously wrote (in his preface to Pygmalion) that it is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him. The Irish shouldn't be so smug. A few years ago, my solicitor in Dublin committed suicide when he was about to be exposed for serious financial irregularities. One of the national newspapers, not even attempting to hide its its schadenfreude, wrote that he "seemed to be the epitome of protestant respectability". Do I note similar slippage in the DIB's entry on John Brougham the actor-playwright: "born ... in what appears to have been a respectable protestant family"? Let it pass: Brougham (pictured) is more interesting. A rival of Dion Boucicault, he claimed to have co-written one his his hit plays, London Assurance, although he lost a lawsuit pressing his claim. Like Boucicault, he had hits in Dublin, London and New York, and was a prolific writer, responsible for more than 160 plays and other stage works. He performed oratory by Daniel O'Connell and the temperance campaigner Father Mathew, dramatized popular novels such as David Copperfield and created hit burlesques. The DIB believes that in one burlesque, PO-CO-HON-TAS, this southern anthem Dixie was "introduced" but I believe it predated the show by a couple of years. Regardless, PO-CO-HON-TAS was a big and long-running hit: it even opened Dublin's Gaiety Theatre, still standing, in 1872. His personal life was less complicated than Boucicault's, although he is described as being "[g]enerous, extravagant, and improvident, and noted for helping others get rich while he got poorer."

We're probably all familiar with the story of Christy Brown, from his memoir My Left Foot and Jim Sheridan's film of the same title with Daniel Day-Lewis. It's worth recalling though: one of 22 children of a Dublin bricklayer, of which 13 survived, he was paralyzed from birth, except for the use of the famous foot. He began using it to write with chalk, then started painting at the age of 10. His memoir, published when he was 22, was followed by novels and poetry and his painting were widely exhibited. Not surprisingly, he could be "moodily cantankerous and obstinate", although he could also be "witty and gregarious".

I've mentioned before that the cutoff date for the DIB is 2002, by which you have to be dead to be considered for inclusion. This generally means that you have to be antique, but still leaves room for a few who died before their time. Thus we have a contemporary figure, Jimmy Brown, "republican socialist and drug-dealer". The Northern Ireland Troubles through up a toxic mixture of guerrillas, politicos, gangsters and psychopaths, sometimes all incarnated in the same person. Brown's breakaway Irish Republican Socialist Party and its military wing, the Irish National Liberation Army, engaged fully in killing unionists, as well as those nominally on its own side who had committed ideological or other crimes. They took up drug dealing to raise money for arms, and had the bright idea of recruiting people who knew how to deal drugs, i.e. criminals. This of course caused them huge problems in the communities were the drugs were dealt, notably their own. Certain loyalists did the same thing, and the war of national liberation descended into something much uglier: a gangsters' turf war. Jimmy Brown was finally liquidated by the IRA, which had lost patience with the various splinter groups. The DIB's Patrick Maume writes well that he was a "devious man who deceived himself [and] provided an ideological veneer for sectarian murder and criminality". Ugly times.

The Lithuanian revolutionary, a family of artists, the upper-crust hardliner and the shoe-burning paterfamilias

Robert Emmet Briscoe. The first two names are those of a venerated Irish patriot, executed after an abortive uprising of 1803 but celebrated for a fine parting speech. The last name: it's interesting. The dictionaries say that Briscoe is a Yorkshire-Cumberland name, derived from the Norse, meaning the place of birch wood. But Robert Emmet Briscoe's people probably never went near Yorkshire or Cumberland: they were Lithuanians, from a shtetl in the province of Kovno, in the tsarist pale of settlement in which Jews were concentrated. I don't know the Lithuanian original of Briscoe, but it may well have been closer to its Irish version than my surname, Grantham, which my father took from a book to supplant his Hungarian-Jewish name, Gross (originally Grosz). Robert's father Abraham arrived in Dublin at the age of 14, part of the great late-19th century migration of Jews from the pale of settlement, of which a number wound up in Ireland. (Between 1871 and 1911, the Jewish population of Dublin rose from 189 to 2,965: the total population of the city in 1911 was around 350,000.) Somewhere along the line, Abraham added Irish nationalism to his fairly strict religious observances, which resulted in Robert's patriotic name, as well as that of his brother, Wolfe Tone Briscoe.

After the Easter rising, Briscoe embraced physical force nationalism and returned to Ireland from the USA, where he had run a Christmas light business. He rose in the nationalist movement, but his origins were not always overlooked: we've already seen how another leading nationalist, Charles Bewley, expressed his anti-semitism openly to Briscoe. It can't have been easy: another important nationalist, George Gavan Duffy, attempted to enlist the support of the Vatican behind the independence movement by informing it that "Jews and Masons were united against us in foreign press in support of England." But Briscoe stuck it out, and was elected to the Dáil for a Dublin constituency in 1927: between Robert and his son Ben, the family held the seat for 75 years. We've also seen how Robert advocated the admission of Jewish refugees to Ireland before, during and after the Second World War, with some limited success.

After Ireland, his biggest enthusiasm was for Zionism, which leads to some interesting parallels. One thing Briscoe knew a bit about was revolutionary war. He embraced Ze'ev Jabotinsky's ideology of revisionist zionism (the DIB refers to Jaboinsky's Revisionist Party, but the political body was called the New Zionist Organization) and advised its military wing, the Irgun, on military matters, including the conduct of a guerrilla war. Although this war in the years up to the foundation of the state of Israel was in part being waged against the British, the principal victims of Irgun attacks were Palestinian arabs: abaout 500 dead between 1937 and 1948. According to the DIB, after the Second World War, Briscoe advised the Irgun leader Menachem Begin to emulate De Valera and embrace parliamentary politics: in that sense, Likud is the Fianna Fáil of modern Israel.

Late in life, Briscoe became a sensation in the USA, where he toured during his tenure as Lord Mayor of Dublin. Even now, more than 50 years later, alter kockers still bring up Briscoe as one of the few Irishmen they've ever heard of. Improbably, Briscoe's American reputation was so high, that an episode of CBS's legendary Playhouse 90 series was devoted to him, directed by John Frankenheimer with, even more improbably, the very goyisch Irish-American Art Carney in the leading role. Apparently at one point in the play, he recites the prayer for the dead, the kaddish, in Hebrew. That, I would have liked to see. (By the way, my attempted embrace of Yiddish is completely phony: Hungarian Jews largely spoke ... Hungarian.)

I'm indebted to a website called the Irish Comics Wiki for this 1810 illustration, by the caricaturist Henry Brocas, Sr., who produced lively political stuff as well as more formal portraiture, including of Robert Emmett, who bestowed his names on Robert Briscoe, above. He found employment running an art college in Dublin, but was fired for being "erratic", unpunctual, insubordinate and disobedient. The family was very gifted: Henry's brother, Arthur, was also an artist, as were his four sons, including Henry junior, who emulated his father in another respect: he rose to take charge of the same art college, the Royal Dublin Society's School of Landscape and Ornament, only also to be dismissed for his failings in the post.

It's striking how many high-bred Irish women embraced nationalism at the turn of the 20th century. We've already encountered the Gore-Booth sisters; among many others was Albinia Brodrick born in London, daughter of Viscount Midleton. She came to know Ireland through visits to the family's estate in Co. Cork; her brother William was a leading unionist. I had forgotten that I encountered Albinia once before, in Hubert Butler's marvelous essays - in her case, in the autobiographical one called "The Auction" collected in his book Grandmother and Wolfe Tone - in which it was said of her that she

The Brookes received their estates first in Donegal as a reward for military service in the early 17th century and then in Fermanagh following the 1641 rebellion. They were soldiers - 53 of them served in the First and Second World Wars, one, Alan, as the chief of the imperial general staff. They were politicians in the protestant interest, and Orangemen, and the family's unionism became more strident as militant nationalism grew in the late 19th century. Alan's nephew, Basil, was a typical Brooke, who served in the army and became increasingly involved in Irish affairs on his trips home to visit the family estates, which he had inherited. When he settled down in Fermanagh in 1918 he had, as the DIB puts it, "been elsewhere for most of the previous twenty-two years." He organized militias to oppose the emerging IRA military campaign, and after partition was elected to the Northern Ireland parliament, ultimately serving as prime minister for 20 years until 1963. He embraced the sectarianism that was essential to the career of any successful unionist politician, telling supporters "to employ good protestant lads and lassies" only. While he was prime minister, catholic grievances festered: as the DIB describes them, "the restricted local government franchise, gerrymandered electoral boundaries, religious discrimination in public bodies and private firms, and perceived shortfalls in the funding for private schools." He also resisted modernizers in his party who wished to recruit catholics. "It is difficult not to conclude," writes the DIB's Brian Barton, "that he lacked that higher quality of leadership that does not simply reflect and pander to its supporters but dares to challenge and dispel their prejudices." Naturally, he was ennobled, knighted and otherwise lavishly honored in recognition of his service.

After the Easter rising, Briscoe embraced physical force nationalism and returned to Ireland from the USA, where he had run a Christmas light business. He rose in the nationalist movement, but his origins were not always overlooked: we've already seen how another leading nationalist, Charles Bewley, expressed his anti-semitism openly to Briscoe. It can't have been easy: another important nationalist, George Gavan Duffy, attempted to enlist the support of the Vatican behind the independence movement by informing it that "Jews and Masons were united against us in foreign press in support of England." But Briscoe stuck it out, and was elected to the Dáil for a Dublin constituency in 1927: between Robert and his son Ben, the family held the seat for 75 years. We've also seen how Robert advocated the admission of Jewish refugees to Ireland before, during and after the Second World War, with some limited success.

After Ireland, his biggest enthusiasm was for Zionism, which leads to some interesting parallels. One thing Briscoe knew a bit about was revolutionary war. He embraced Ze'ev Jabotinsky's ideology of revisionist zionism (the DIB refers to Jaboinsky's Revisionist Party, but the political body was called the New Zionist Organization) and advised its military wing, the Irgun, on military matters, including the conduct of a guerrilla war. Although this war in the years up to the foundation of the state of Israel was in part being waged against the British, the principal victims of Irgun attacks were Palestinian arabs: abaout 500 dead between 1937 and 1948. According to the DIB, after the Second World War, Briscoe advised the Irgun leader Menachem Begin to emulate De Valera and embrace parliamentary politics: in that sense, Likud is the Fianna Fáil of modern Israel.

Late in life, Briscoe became a sensation in the USA, where he toured during his tenure as Lord Mayor of Dublin. Even now, more than 50 years later, alter kockers still bring up Briscoe as one of the few Irishmen they've ever heard of. Improbably, Briscoe's American reputation was so high, that an episode of CBS's legendary Playhouse 90 series was devoted to him, directed by John Frankenheimer with, even more improbably, the very goyisch Irish-American Art Carney in the leading role. Apparently at one point in the play, he recites the prayer for the dead, the kaddish, in Hebrew. That, I would have liked to see. (By the way, my attempted embrace of Yiddish is completely phony: Hungarian Jews largely spoke ... Hungarian.)

I'm indebted to a website called the Irish Comics Wiki for this 1810 illustration, by the caricaturist Henry Brocas, Sr., who produced lively political stuff as well as more formal portraiture, including of Robert Emmett, who bestowed his names on Robert Briscoe, above. He found employment running an art college in Dublin, but was fired for being "erratic", unpunctual, insubordinate and disobedient. The family was very gifted: Henry's brother, Arthur, was also an artist, as were his four sons, including Henry junior, who emulated his father in another respect: he rose to take charge of the same art college, the Royal Dublin Society's School of Landscape and Ornament, only also to be dismissed for his failings in the post.

It's striking how many high-bred Irish women embraced nationalism at the turn of the 20th century. We've already encountered the Gore-Booth sisters; among many others was Albinia Brodrick born in London, daughter of Viscount Midleton. She came to know Ireland through visits to the family's estate in Co. Cork; her brother William was a leading unionist. I had forgotten that I encountered Albinia once before, in Hubert Butler's marvelous essays - in her case, in the autobiographical one called "The Auction" collected in his book Grandmother and Wolfe Tone - in which it was said of her that she

[C]onceived it her mission to atone for the sins of her ancestor, exacting landlords of the south-west; she dressed as an old Irish countrywoman and ran a village shop, while behind her on a stony Dunkerron promontory rose the shell of a large hospital which she had built for the sick poor of Kerry, but which, because of its unsuitable though romantic site, had remained empty and unused.Butler made her seem a merely local curiosity; in fact, she plunged into national politics, supporting the Easter rising and visiting republican prisoners. She took the name Gobnait Ní Bhruadair, opposed the Anglo-Irish treaty, and during the civil war was shot in the leg by Free State forces. At the same time, she was a stalwart of her local protestant church, where she played the harmonium (while requiring her catholic employees to attend mass. The DIB says that she was "difficult and eccentric"; she left most of her estate to republicans "as they were in the years 1919 to 1921" - a bequest that a court ruled was "void for remoteness". Butler, writing of her failed hospital, could have been summing her up as well:

There is a labyrinthine story of idealism, obstinacy, perversity, social conscience, medicine, family, behind this empty structure. The man who could unravel it would be diagnosing the spiritual sickness of Ireland ...The Brontë sisters had a Brontë father, and he was Irish. Patrick Brontë started out as Patrick Prunty (the DIB also has Brunty, which I hadn't previously seen), a farm laborer's son from Co. Down. He seems to have been lucky in his clerical friends: one presbyterian minister tutored him and found him a job as a teacher (he was fired for an affair with a pupil) while an anglican one obtained a scholarship to Cambridge for him, where he changed his name in recognition of Admiral Nelson, who had been named Duca di Bronte by King Ferdinand of Italy. Once ordained, he found himself eventually in Yorkshire, where according to Elizabeth Gaskell he lost all traces of his Irish accent. The DIB entry doesn't mention this, nor Mrs Gaskell's claims that Brontë burned his children's brightly-colored boots because they were too showy, or that he fired pistols outside the back door of the Haworth parsonage to dissipate his "volcanic wrath". He bore the death of his wife and all four of his very talented children before dying at the age of 84.

The Brookes received their estates first in Donegal as a reward for military service in the early 17th century and then in Fermanagh following the 1641 rebellion. They were soldiers - 53 of them served in the First and Second World Wars, one, Alan, as the chief of the imperial general staff. They were politicians in the protestant interest, and Orangemen, and the family's unionism became more strident as militant nationalism grew in the late 19th century. Alan's nephew, Basil, was a typical Brooke, who served in the army and became increasingly involved in Irish affairs on his trips home to visit the family estates, which he had inherited. When he settled down in Fermanagh in 1918 he had, as the DIB puts it, "been elsewhere for most of the previous twenty-two years." He organized militias to oppose the emerging IRA military campaign, and after partition was elected to the Northern Ireland parliament, ultimately serving as prime minister for 20 years until 1963. He embraced the sectarianism that was essential to the career of any successful unionist politician, telling supporters "to employ good protestant lads and lassies" only. While he was prime minister, catholic grievances festered: as the DIB describes them, "the restricted local government franchise, gerrymandered electoral boundaries, religious discrimination in public bodies and private firms, and perceived shortfalls in the funding for private schools." He also resisted modernizers in his party who wished to recruit catholics. "It is difficult not to conclude," writes the DIB's Brian Barton, "that he lacked that higher quality of leadership that does not simply reflect and pander to its supporters but dares to challenge and dispel their prejudices." Naturally, he was ennobled, knighted and otherwise lavishly honored in recognition of his service.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

An effective diplomat, two legends of Hollywood and two legends of history

(A quick word about pictures. I do my best to find pictures that are, first, actually of the person discussed and, second, in the public domain. Neither of these tasks is straightforward. In the case of the adjacent photo, I'm really proceeding on faith and it might be a dentist from Dusseldorf: read and view at your own risk.) Maeve Brennan's father, Robert, like so many in the DIB, started out quite conventionally and found his life transformed by revolution. He was from Wexford, worked for the county council and became a local newspaper reporter. As a 35-year-old revolutionary, married with two children, he was sentenced to death for his part in the 1916 rising , and when his sentence was commuted, served time in prison in England and upon his release became involved in international relations for the revolutionary government, travelling to the United States and France. After starting the Irish Press newspaper, he joined the Irish Free State's diplomatic service in 1934 and was posted to Washington DC, where he rose to the rank of minister. This became a very tricky job after 1941, when the USA entered the Second World War while Ireland remained neutral, with German, Italian and Japanese diplomats remaining in Dublin. In 1944, at the behest of the U.S. Amabssador David Grey, who was - unfortunately for Ireland - both close to Franklin Roosevelt and unsympathetic to the Taoiseach, Eamon De Valera, delivered a diplomatic note calling for the expulsion of Axis diplomats from Ireland, which note he immediately leaked to the press. The note caused uproar in Britain and America, and Ireland's reputation in public opinion sagged. However the note caused a much bigger problem: the U.S. and British security services were at the time highly satisfied with the sub rosa cooperation they were receiving from their Irish counterparts and were horrified that this diplomatic démarche might undermine it. Brennan worked in Washington to educate the State Department - whose officials were not always abreast of security matters - to the extent that Grey had to admit that he had not known of the degree of cooperation at the time he delivered the note. (Not everybody will agree with this assessment, but recent archival research tends to support it.) On top of all that, Brennan published novels and memoirs, and wrote two plays, one of which was performed at the Abbey.

My friends, the late journalist Steve Brennan and his wife Bernadette O'Neill put together a very good book, Emeralds in Tinseltown: The Irish in Hollywood, that begins its story in the earliest days of the film business. Hubert Brenon from Dublin, virtually forgotten today, was directing Mary Pickford films for Carl Laemmle before Hollywood even existed: it's been claimed he directed more than 300, most of them lost. He gave early leading roles to Theda Bara, Pola Negri, Ronal Colman, Clara Bow and Lon Chaney. According to Emeralds in Tinseltown, but not the DIB, Brenon sued the mogul William Fox when his directing credit was removed from the over-budget (but smash hit) Daughter of the Gods (1916): he was unsuccessful but the lawsuit emboldened directors to insist on credit in their studio contracts. Like so many, including his great countryman the director Rex Ingram, Brenon's career did not survive the transition to sound, although he made a steady stream of films in England until 1940. He died in Hollywood in 1958.

More Hollywood: the DIB's a little hard on George Brent (pictured here with his second wife Ann Sheridan). Born George Nolan in Co. Galway, he played at the Abbey Theatre but skipped out to Canada when suspected of IRA activity (you never know how true these stories - he appears to be the source for this one). While he was never a screen legend like Clark Gable, he was leading man to a host of the best Hollywood actresses including Greta Garbo, Merle Oberon, Olivia de Havilland, Barbara Stanwyck and, above all, Bette Davis, with whom he appeared 11 times, including in the sublime Jezebel and Dark Victory. The DIB is a little quick to push him off his pinnacle: even though he obtained fewer leading roles as he grew older, he still had large parts in major studio pictures until the late 1940s, and some the work of his "severe decline" is nonetheless interesting, including The Last Page, Terence Fisher's first film for Hammer Pictures, with a script by Frederick Knott (Dial M For Murder, Wait Until Dark) based on a play by James Hadley Chase (No Orchids for Miss Blandish). His post-movies television career was distinguished enough to earn him a second star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Still, as it must to all actors, obscurity finally descended on George Brent: after a spell of horse breeding, he died of emphysema in 1979.

Remember what I said about pictures? I don't claim that this is actually a picture taken from life of the High King Brian Boru, or Brian Bórama, as he's more accurately known (it means Brian from Bórama, a place near Killaloe in Co. Clare). He died in 1014 at the Battle of Clontarf at which the Irish defeated the Vikings outside Dublin. I still have my history textbook from national school 45 years ago, by "D. Casserley, M.A.", an interesting woman I would have like to have seen in the DIB. She tells the story all Irish children learned, and maybe still learn: how Boru united the Irish under a single High King and then broke the political power of the Viking invaders, dying at the moment of his triumph. It's quite a nuanced account for a book aimed at elementary schoolchildren (for instance, wondering if Boru felt any pangs of conscience about overthrowing his nearest rival - "we can only hope he did"). The DIB gives him his due - "an outstanding success" and "the most powerful of rules in his day" - while noting shrewdly that the image that grew after his death was one he himself had begun to cultivate beforehand.

Another legendary Irish figure: St. Brigit. This is what D. Casserley, M.A. had to say about her:

My friends, the late journalist Steve Brennan and his wife Bernadette O'Neill put together a very good book, Emeralds in Tinseltown: The Irish in Hollywood, that begins its story in the earliest days of the film business. Hubert Brenon from Dublin, virtually forgotten today, was directing Mary Pickford films for Carl Laemmle before Hollywood even existed: it's been claimed he directed more than 300, most of them lost. He gave early leading roles to Theda Bara, Pola Negri, Ronal Colman, Clara Bow and Lon Chaney. According to Emeralds in Tinseltown, but not the DIB, Brenon sued the mogul William Fox when his directing credit was removed from the over-budget (but smash hit) Daughter of the Gods (1916): he was unsuccessful but the lawsuit emboldened directors to insist on credit in their studio contracts. Like so many, including his great countryman the director Rex Ingram, Brenon's career did not survive the transition to sound, although he made a steady stream of films in England until 1940. He died in Hollywood in 1958.

More Hollywood: the DIB's a little hard on George Brent (pictured here with his second wife Ann Sheridan). Born George Nolan in Co. Galway, he played at the Abbey Theatre but skipped out to Canada when suspected of IRA activity (you never know how true these stories - he appears to be the source for this one). While he was never a screen legend like Clark Gable, he was leading man to a host of the best Hollywood actresses including Greta Garbo, Merle Oberon, Olivia de Havilland, Barbara Stanwyck and, above all, Bette Davis, with whom he appeared 11 times, including in the sublime Jezebel and Dark Victory. The DIB is a little quick to push him off his pinnacle: even though he obtained fewer leading roles as he grew older, he still had large parts in major studio pictures until the late 1940s, and some the work of his "severe decline" is nonetheless interesting, including The Last Page, Terence Fisher's first film for Hammer Pictures, with a script by Frederick Knott (Dial M For Murder, Wait Until Dark) based on a play by James Hadley Chase (No Orchids for Miss Blandish). His post-movies television career was distinguished enough to earn him a second star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Still, as it must to all actors, obscurity finally descended on George Brent: after a spell of horse breeding, he died of emphysema in 1979.

Remember what I said about pictures? I don't claim that this is actually a picture taken from life of the High King Brian Boru, or Brian Bórama, as he's more accurately known (it means Brian from Bórama, a place near Killaloe in Co. Clare). He died in 1014 at the Battle of Clontarf at which the Irish defeated the Vikings outside Dublin. I still have my history textbook from national school 45 years ago, by "D. Casserley, M.A.", an interesting woman I would have like to have seen in the DIB. She tells the story all Irish children learned, and maybe still learn: how Boru united the Irish under a single High King and then broke the political power of the Viking invaders, dying at the moment of his triumph. It's quite a nuanced account for a book aimed at elementary schoolchildren (for instance, wondering if Boru felt any pangs of conscience about overthrowing his nearest rival - "we can only hope he did"). The DIB gives him his due - "an outstanding success" and "the most powerful of rules in his day" - while noting shrewdly that the image that grew after his death was one he himself had begun to cultivate beforehand.

Another legendary Irish figure: St. Brigit. This is what D. Casserley, M.A. had to say about her:

Bridgid, who was the daughter of a nobleman, was born at Faughart, near Dundalk, a few years before St. Patrick's death. When she grew up, she determined to devote her life to God's service, so she became a nun, and did splendid work among the poor, as well as converting many of the pagan Irish, of whom there were still a great number. The monastery which she founded was called Cill Dara (the Church of the Oak Tree), and it is from it that Kildare gets its name. Many stories are told of St. Brigid's goodness to the poor, and her love of children and animals. Under her wise and gentle rule the monastery and convent of Kildare were renowned throughout Ireland.The DIB harshes this buzz. Here is how its entry begins: "BRIGIT (Brighid, Brid, Bride, Bridget) (possibly c.450-524), reputed foundress and first abbess of Cell Dara (Kildare), is the female patron saint of Ireland, but it is uncertain whether she existed as a person." Oh well. She is posited as more likely a "ghost personality", founded a pagan goddess, also Brigit, who was used as an exemplar in the transition to Christianity. This did not prevent - or perhaps is the reason for - her cult becoming widespread and her name being given to a large number of places, churches, wells and the like in Ireland and in places where the Irish went. I always liked her feast day, February 1, since it marked the beginning of the end of winter, when snowdrops would push through the melting snow, the first sign of the renewal of spring. It's a long time since I've seen a snowdrop, but I always think of them at this time of year, so here's a picture. A real one, I think.

Two film censors, a long-winded lady and the first Irish bandmeister

The newly-independent Irish state threw itself with heroic energy into banning anything that would undermine its leaders' sense of what the nation should be. That sense was very, very narrow, catholic, conservative, anti-sex and anti-cosmopolitan. My father wrote a very popular series, The Kennedys of Castleross, for Irish radio beginning in the 1950s, and there were certain subjects that simply could not be mentioned. Pregnancy, for instance, despite it's being a subject which which most Irish families were readily and frequently familiar. But on the radio, it was only to be broached by implication. E.g., "I've just been to see the doctor." "What did he say?" "Well ..." "You're not! You are? How wonderful!!!" Cue music.

In the first 70 years of the state, Ireland's censors banned 2,500 films and between 10,000 and 11,000 more were cut. (According to the critic Ciaran Carty, by 1961, Ireland's separate banned book list contained more than 10,000 titles, including works by Faulkner, Sartre, Thomas Mann, Hemingway and Steinbeck.) At the outset, the censors had no background in film. Martin Brennan, the third such, appointed in 1954, had had a "good war" during the independence campaign, became a doctor and went into politics. In office, he banned Luis Buñuel's Los Olvidados and Laughton's Night of the Hunter, among many others. He banned Edward Dmytryk's adaptation of Graham Greene's The End of the Affair, citing "theological implications which are far above the normal cinemagoer's ability to grasp." He also refused to permit depictions of the Eucharist, even in newsreels.

Dermot Breen, appointed in 1972, was a man of the cinema, having founded the Cork Internaitonal Film Festival. He banned Pasolini's Decameron, Ken Russell's The Devils, Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange and Fellini's Roma. (To be fair, at the time many of these ran into censorship trouble elsewhere, including in the UK.) Like Brennan, his piety also found some film depictions of catholicism troubling, a sentiment that influenced his official actions. Yet Breen's period as censor was considered to be an improvement on those of his predecessors, and it probably was. It took until 1992 for a year to pass in which no film was cut or banned by the Irish state.

Maeve Brennan was scarcely known in Ireland until after her death in 1993. She had lived in the USA from the age of 17, when her father was appointed secretary of the Irish legation in Washington DC. After graduating from college, she moved to New York to become a librarian. But she crossed into journalism, first at Harper's Bazaar and then at the New Yorker, during the golden age of its great editor, William Shawn, who recruited her in 1949. Her non-fiction essays under the title "The Long-Winded Lady" are deft miniatures of city life where small details - how to eat broccoli in a restaurant, for instance - become slyly indexed to big questions, such as how to live. Her short stories, first collected in a volume entitled In And Out of Never-Never Land, similarly build from small observations and events - a child finding a book of damp matches, say - to dramatic and emphatic discoveries. Many of her stories were about Ireland, including Wexford where her parents were born and Dublin where she was raised, as well as about the Irish in America. She was beautiful, footloose, self-isolating, alcoholic and, ultimately and sadly, mad.

I've mentioned the Irish nazi thing a couple of times before, and said I'd return to it, this time just in passing. A small Dublin pleasure during the short Irish summer is to sit in St Stephen's Green park at lunchtime and listen to the Army No. 1 Band. The music is mellow and good-natured, and, as befits the representatives of a very small army, does not seem to prefigure a massive fire attack by squadrons of helicopter gunships. The first officer to command the Irish army school of music, through which the band was organized, was Wilhelm Fritz Brase, who had been a leading bandmaster in the imperial German army and the Berlin police. He was very effective, recruiting performers, giving recitals, getting involved in the early days of radio broadcasting and training enough musicians that he was able to create three further bands. (I wasn't able to find examples of Brase's own compositions, which included six fantasias on Irish themes, but I did uncover a recording that he conducted of German military music before he moved to Ireland, which is quite jolly, as well as his official arrangement of the Irish national anthem, performed by the Army band - don't forget to stand when you listen to it.) The nazi party's overseas organization, the auslandsorganisation, invited him to be chairman of its Irish branch, but the army refused him permission to do so. Hitler did, however, confer on him the honorific title of Professor. Fritz Brase died in 1940. Whatever else he stood for, he did a great job on the Army band, for which I thank him.

In the first 70 years of the state, Ireland's censors banned 2,500 films and between 10,000 and 11,000 more were cut. (According to the critic Ciaran Carty, by 1961, Ireland's separate banned book list contained more than 10,000 titles, including works by Faulkner, Sartre, Thomas Mann, Hemingway and Steinbeck.) At the outset, the censors had no background in film. Martin Brennan, the third such, appointed in 1954, had had a "good war" during the independence campaign, became a doctor and went into politics. In office, he banned Luis Buñuel's Los Olvidados and Laughton's Night of the Hunter, among many others. He banned Edward Dmytryk's adaptation of Graham Greene's The End of the Affair, citing "theological implications which are far above the normal cinemagoer's ability to grasp." He also refused to permit depictions of the Eucharist, even in newsreels.

Dermot Breen, appointed in 1972, was a man of the cinema, having founded the Cork Internaitonal Film Festival. He banned Pasolini's Decameron, Ken Russell's The Devils, Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange and Fellini's Roma. (To be fair, at the time many of these ran into censorship trouble elsewhere, including in the UK.) Like Brennan, his piety also found some film depictions of catholicism troubling, a sentiment that influenced his official actions. Yet Breen's period as censor was considered to be an improvement on those of his predecessors, and it probably was. It took until 1992 for a year to pass in which no film was cut or banned by the Irish state.

Maeve Brennan was scarcely known in Ireland until after her death in 1993. She had lived in the USA from the age of 17, when her father was appointed secretary of the Irish legation in Washington DC. After graduating from college, she moved to New York to become a librarian. But she crossed into journalism, first at Harper's Bazaar and then at the New Yorker, during the golden age of its great editor, William Shawn, who recruited her in 1949. Her non-fiction essays under the title "The Long-Winded Lady" are deft miniatures of city life where small details - how to eat broccoli in a restaurant, for instance - become slyly indexed to big questions, such as how to live. Her short stories, first collected in a volume entitled In And Out of Never-Never Land, similarly build from small observations and events - a child finding a book of damp matches, say - to dramatic and emphatic discoveries. Many of her stories were about Ireland, including Wexford where her parents were born and Dublin where she was raised, as well as about the Irish in America. She was beautiful, footloose, self-isolating, alcoholic and, ultimately and sadly, mad.

I've mentioned the Irish nazi thing a couple of times before, and said I'd return to it, this time just in passing. A small Dublin pleasure during the short Irish summer is to sit in St Stephen's Green park at lunchtime and listen to the Army No. 1 Band. The music is mellow and good-natured, and, as befits the representatives of a very small army, does not seem to prefigure a massive fire attack by squadrons of helicopter gunships. The first officer to command the Irish army school of music, through which the band was organized, was Wilhelm Fritz Brase, who had been a leading bandmaster in the imperial German army and the Berlin police. He was very effective, recruiting performers, giving recitals, getting involved in the early days of radio broadcasting and training enough musicians that he was able to create three further bands. (I wasn't able to find examples of Brase's own compositions, which included six fantasias on Irish themes, but I did uncover a recording that he conducted of German military music before he moved to Ireland, which is quite jolly, as well as his official arrangement of the Irish national anthem, performed by the Army band - don't forget to stand when you listen to it.) The nazi party's overseas organization, the auslandsorganisation, invited him to be chairman of its Irish branch, but the army refused him permission to do so. Hitler did, however, confer on him the honorific title of Professor. Fritz Brase died in 1940. Whatever else he stood for, he did a great job on the Army band, for which I thank him.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

The lost tribesman, a fugitive from abstract expressionism, the senior Steptoe and the Hitler-loving cop

During the Troubles, it was always striking to me how many of the most strident voices belonged to clergy. My mother was very keen on the Sermon on the Mount, and I always took seriously such Christian invocations are "love thine enemy" and "blessed are the peacemakers". So, I found it bothersome that these elemental principles seemed to be lost on so many of the dog-collar-sporting leaders of Northern Ireland politics. Ian Paisley, of course, was the most prominent. But then there was Robert Bradford. He had briefly been a professional soccer player after which he studied for the ministry - as a methodist, not a presbyterian like most other protestant hardliners. (He was ultimately removed by the church from his position.) His political success depended on refusing any accommodation with the catholic minority and was generally out on the fringes of a wide range of issues. (The DIB does not repeat the apparently documented claim that on one occasion Bradford provided a written expression of solidarity to the UK neo-fascist party the National Front.) For a while he made, but subsequently trimmed, the claim that Ulster protestants were descended from the lost tribe of Israel. His crazy extremism was said to be expressed with a "mild, shy demeanour." The IRA assassinated him in 1981, triggering a horrible escalation of inter-communal violence: his seat in the British parliament was won by another clerical extremist, Martyn Smith. With apologies to my mother (and Christ), I'm afraid that Robert Bradford stretched all my efforts to love enemies to - and beyond - the limit.

For the first time so far in the DIB: someone I knew. Charles Brady - Charlie to us - was an Irish-American painter who moved to Ireland in the 1950s and stayed. A New Yorker like my father, the two formed a real bond. I remember one night when I was about 17, and Charlie was over in London, visiting. It was a Sunday, and I was meant to be cooking dinner. The two of them became roaring drunk at the Chelsea Arts Club and got themselves into a scrape shinning up drainpipes, climbing ivy or some other form of vertical scaling to get into an upstairs window - the stairs being for some reason unavailable to them. They finally turned up giggling two or three hours late with the dinner cold: I began to see the world for the first time from my mother's point of view. Charlie, who became an honorary member of the Royal Hibernian Academy, was a very fine painter. He had studied in New York at the Art Students League and was the contemporary of Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, all of whom he knew. He told my father that one of the reasons he left New York was that he felt crowded by the ascendancy of abstract expressionism. Instead, he was interested in figuration, painting series of simple scenes, such as wire hangers in cupboards, envelopes leaning against walls, or balls of wool on the floor. However, as the DIB entry, by Rebecca Minch, shrewdly points out, the flat simplicity of Charlie's work owed more than a little to his abstract expressionist classmates. (I was a little severe on Minch's account of W.H. Bartlett: this entry, excellent, is of a different order.) He was an exotic figure to me: gaunt, redfaced, always smoking long American cigarettes. He was very kind, and gave my father three wonderful paintings which hang in the house in Greystones. I was told that he refused to price his work high, even when, late in life, there was serious collector interest in it, including from the politician Charles Haughey, whose utter corruption did not efface quite good taste in art. Charlie - Brady, not Haughey - preferred that people could afford his paintings and insisted that his dealer price them accordingly.

For years in my childhood, the funniest show on TV, at least in my household, was Steptoe & Son, a BBC comedy about a father and son running a rag and bone business. The father, Albert Steptoe, was an insanitary, grasping, manipulative monster, while Son, Harold, was a footloose, fantasizing co-dependent, dreaming of cutting family strings that would always remain uncut. They were a sublime double act, a delirious cross between Samuel Beckett, kitchen sink drama and the Ealing comedies. Living on the east coast of Ireland in the 1960s, we were able to pick up BBC transmissions from the UK and would rarely miss an episode; we kept it up once we moved to England. Families still gathered to watch television then, and Steptoe was a pleasure we always tried to take together. Albert Steptoe was played by Wilfrid Brambell, a Dublin actor who became successful in England in old man roles, even when he was quite young - he was only 50 when he began to play Albert, in 1962. (He was a memorable old man in Richard Lester's Beatles film, A Hard Day's Night.) Apparently, he was really impossible. He drank too much and hated his co-star, Harry H Corbett, who hated him back. He was so difficult, that serious thought was given to sacking him in 1965, despite the huge success of the series. A gay man at the time when homosexual practices were illegal, his Ortonesque lifestyle also carried risks of arrest and exposure that he did not often skirt well, although he found love later in life. (A 2008 BBC film, The Curse of Steptoe, dramatized the story.) We viewers, fortunately, knew none of this: we just laughed like drains at one of the funniest things we'd ever seen. Harold's absurd hipster pretensions, driving his horse and cart through Swinging London, constantly brought down by the malign machinations of his father, brilliantly captured the contradictions and pain of the age, and life.

"Lugs" Branigan. They don't make coppers like him any more, thank God. He took up boxing to fend off bullies, and became an international heavyweight, although not a particularly good one: during a fight in Germany in 1938, in the presence of Goebbels and Goering, he was knocked down nine times and got up after every flooring. I wonder if it was the good-natured applause of the crowd that endeared the nazi regime to him: the DIB reports that while "he disagreed with Hitler's anti-semitism he kept a scrapbook of his career and regarded him as 'a great man'". The DIB's indulgence continues: "Rather than charging offenders, he admitted that he usually gave them 'a bit of a going over' and sent them on their way to avoid excessive paperwork". He hated the nickname "Lugs", an ear-related slur, and those who uttered it could expect "a few clips". (He preferred "Jim".) Upon his retirement, he received a gift of cutlery and Waterford crystal from Dublin prostitutes, many of whom, it says here, "regarded him as a father figure". In retirement, he bred budgerigars.

For the first time so far in the DIB: someone I knew. Charles Brady - Charlie to us - was an Irish-American painter who moved to Ireland in the 1950s and stayed. A New Yorker like my father, the two formed a real bond. I remember one night when I was about 17, and Charlie was over in London, visiting. It was a Sunday, and I was meant to be cooking dinner. The two of them became roaring drunk at the Chelsea Arts Club and got themselves into a scrape shinning up drainpipes, climbing ivy or some other form of vertical scaling to get into an upstairs window - the stairs being for some reason unavailable to them. They finally turned up giggling two or three hours late with the dinner cold: I began to see the world for the first time from my mother's point of view. Charlie, who became an honorary member of the Royal Hibernian Academy, was a very fine painter. He had studied in New York at the Art Students League and was the contemporary of Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, all of whom he knew. He told my father that one of the reasons he left New York was that he felt crowded by the ascendancy of abstract expressionism. Instead, he was interested in figuration, painting series of simple scenes, such as wire hangers in cupboards, envelopes leaning against walls, or balls of wool on the floor. However, as the DIB entry, by Rebecca Minch, shrewdly points out, the flat simplicity of Charlie's work owed more than a little to his abstract expressionist classmates. (I was a little severe on Minch's account of W.H. Bartlett: this entry, excellent, is of a different order.) He was an exotic figure to me: gaunt, redfaced, always smoking long American cigarettes. He was very kind, and gave my father three wonderful paintings which hang in the house in Greystones. I was told that he refused to price his work high, even when, late in life, there was serious collector interest in it, including from the politician Charles Haughey, whose utter corruption did not efface quite good taste in art. Charlie - Brady, not Haughey - preferred that people could afford his paintings and insisted that his dealer price them accordingly.

For years in my childhood, the funniest show on TV, at least in my household, was Steptoe & Son, a BBC comedy about a father and son running a rag and bone business. The father, Albert Steptoe, was an insanitary, grasping, manipulative monster, while Son, Harold, was a footloose, fantasizing co-dependent, dreaming of cutting family strings that would always remain uncut. They were a sublime double act, a delirious cross between Samuel Beckett, kitchen sink drama and the Ealing comedies. Living on the east coast of Ireland in the 1960s, we were able to pick up BBC transmissions from the UK and would rarely miss an episode; we kept it up once we moved to England. Families still gathered to watch television then, and Steptoe was a pleasure we always tried to take together. Albert Steptoe was played by Wilfrid Brambell, a Dublin actor who became successful in England in old man roles, even when he was quite young - he was only 50 when he began to play Albert, in 1962. (He was a memorable old man in Richard Lester's Beatles film, A Hard Day's Night.) Apparently, he was really impossible. He drank too much and hated his co-star, Harry H Corbett, who hated him back. He was so difficult, that serious thought was given to sacking him in 1965, despite the huge success of the series. A gay man at the time when homosexual practices were illegal, his Ortonesque lifestyle also carried risks of arrest and exposure that he did not often skirt well, although he found love later in life. (A 2008 BBC film, The Curse of Steptoe, dramatized the story.) We viewers, fortunately, knew none of this: we just laughed like drains at one of the funniest things we'd ever seen. Harold's absurd hipster pretensions, driving his horse and cart through Swinging London, constantly brought down by the malign machinations of his father, brilliantly captured the contradictions and pain of the age, and life.

"Lugs" Branigan. They don't make coppers like him any more, thank God. He took up boxing to fend off bullies, and became an international heavyweight, although not a particularly good one: during a fight in Germany in 1938, in the presence of Goebbels and Goering, he was knocked down nine times and got up after every flooring. I wonder if it was the good-natured applause of the crowd that endeared the nazi regime to him: the DIB reports that while "he disagreed with Hitler's anti-semitism he kept a scrapbook of his career and regarded him as 'a great man'". The DIB's indulgence continues: "Rather than charging offenders, he admitted that he usually gave them 'a bit of a going over' and sent them on their way to avoid excessive paperwork". He hated the nickname "Lugs", an ear-related slur, and those who uttered it could expect "a few clips". (He preferred "Jim".) Upon his retirement, he received a gift of cutlery and Waterford crystal from Dublin prostitutes, many of whom, it says here, "regarded him as a father figure". In retirement, he bred budgerigars.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

The cheating escheator, the physical lawgiver, the strict disciplinarian and the lying climber

I was watching the England-Wales rugby march today (it happened yesterday, and I recorded it) and noticed something unusual. It was attended by a British princeling - I think it was the one called Prince William - and whenever Wales scored, he stood up, cheered and applauded. Now, I understand that PW is a patron of the Welsh Rugby Union and that his full title is Prince William of Wales. But I think it goes deeper than this: I'm persuaded that he actually believes he is Welsh. His father, of course, as well as being the Duke of Cornwall, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Chester, Earl of Carrick, Baron Renfrew and Lord of the Isles is the Prince of Wales. But he's not exactly Welsh, really, being of direct descent from a German aristocratic family into which occasional vials of English and Scottish DNA have been mixed. William has a spot of Irish, since his grandmother was a Roche whose people hailed from Cork a while back. But there's very little Welsh in the PW family line, at least not since Henry VII (d. 1509), who was born in Wales of a Welsh family. The Welshness of the Waleses is of quite recent vintage: it was that old Cambrian dog Lloyd George who dreamed up the idea of an investiture ceremony in Caernarfon Castle in 1911 for the future Edward VIII and even taught the young prince a few words of his thrust-upon-him native language. The present occupant of the post went through a similar pageant in 1969, for which he studied somewhat more intensively than his great-uncle. PW is thus only the most recent in an invented tradition of Welshification (or maybe mascotification).

I was thinking about this while reflecting on how people became Irish. The DIB, as we've already seen, is full of various arrivistes. This isn't surprising: Ireland is a small place, close to lots of big places, and you'd expect there to be lots of race-mixing to and fro. In fact, despite continuing self-identity as a highly homogeneous people, the Irish are as mongrelized as any: in my own family tree, other than the Hungarians on my father's side (and leaving aside the Greek gods of which I've previously spoken), I'm aware of Huguenot and Scottish heritage diluting my pure Paddytude, and there are probably other, unknown, miscegenating strains. This is fine by me and completely typical. But at the same time, reading Irish lives makes you very aware of those who elbowed their way in, particularly since so many make the kind of impact that gets them an entry in a dictionary of biography.

That's Richard Boyle in the picture: the first earl of Cork, who moved from England to Ireland in 1588, when he was about 22. He got himself a really great job: deputy escheator. Escheat is a feudal concept that still exists in common-law jurisdictions: essentially, it means that if the owner of title to land or other property cannot be found, that land or property "escheats" to the feudal lord, or these days to the state. In late 16th century Ireland, there was a lot of escheating going on, as the English crown looked for reasons to confiscate land from the established Ireland. Boyle was very good at this, and found all sorts of reasons to take land away from people who mistakenly believed they owned it. But once confiscated, he then skimmed, building himself a considerable fortune on the side. He then married another fortune, covering up the fact that his wife's late husband had committed suicide, which was another grounds for escheatment to the crown. His wife then obligingly died, leaving him owner of everything. Not unsurprisingly, these activities annoyed people. It was claimed that some Irish rebels took up arms against the English crown because of Boyle's corrupt activities and accordingly he was charged, convicted and jailed. But by this time he had friends in high places: he was released, pardoned, given a new job, fixed up with a second wealthy wife and a deal to buy Sir Walter Raleigh's estates in Cork for a knockdown price - Raleigh apparently needed the money because he was in prison at the time. (We've come across the Raleigh estate once before: the artist Edith Blake lived in his house near Youghal.) Boyle set about building up his fortune again, breaking Raleigh's leases, either to squeeze more money from the tenants or to put in new ones, usually English soldiers and entrepreneurs keen to loot Munster's rich natural resources. Boyle used the money to buy even more estates in Ireland and England; he also obtained the usual titles to go with his wealth and influence - first a knighthood, then a barony and finally an earldom. Hie second wife obliged him with 15 children of which at least 11 seem to have survived to adulthood. Boyle was energetic in obtaining them wealth and preferment, too, building estates and seeking out advantageous marriages. He lived to the age of 74 and died of natural causes. His family motto was "God's providence is my inheritance." I'm not sure what God had to do with it: the substantial inheritance of his family depended in great part on Boyle's dark genius for business, including a filing system that could keep him up to date on his tenants and their payments "at a moment's notice."

His third son, Roger, was similarly gifted. (The heir, also Richard, merely held on during the political upheavals of his lifetime, adding a second earldom and a viscountcy to his tally of titles.) Roger managed to navigate the turbulent politics of early 17th century Ireland with sinewy talent, switching from monarchy to Commonwealth to restored monarchy with great success. His father obtained for him the title Baron Broghill. The elevation to the earldom of Orrery was all his own work: he married the daughter of the earl of Suffolk and rose and rose and rose. Like his father, some of his wealth was obtained corruptly, although maybe not enough: the cost of his lavish lifestyle consistently exceeded his income. His friends praised his "devising head and towering wit". To these virtues the DIB adds "vanity and deviousness". He played the anti-catholic card whenever he had a chance.

The really talented Boyle was the first Richard's 14th child, Robert, who was born in Cork and became one of the outstanding natural philosophers of an outstanding era. He is the Boyle of Boyle's Law - the one about the proportional relationship between the pressure and volume of a gas - who worked tirelessly in experimental science, particularly chemistry and physics, while also seeking to lead an demanding religious life. Michael Hunter of the DIB nicely links the two strands, stating that "his laboratory practice can in many ways be seen as an extension of his indefatigable examination of his conscience."

The professional descriptions of the DIB continue to be illuminating: thus, you have to read the life of Samuel Boyse, once he's presented as "poet, translator and hack writer", and it's well worth it to discover the life of one whose "destitutions and extravagance were considered infamous even by the standards of eighteenth-century literary bohemia. (He once pawned his clothes and his bed linen and sat in bed writing, wrapped in a blanket.) Similarly, it's irresistible to learn about Reginald Brabazon (pictured) once he's been situated as "landowner, philanthropist and disciplinarian." He founded something called the Duty and Discipline Movement (as well as the Lads' Drill Association), whose aims, according to the DIB, were "to combat softness, slackness, indifference, and indiscipline in young people and to give reasonable support to all legitimate authority." Irresistible or not, I think that reading about him is probably preferable to having been in his company.

Finally, Brendan Bracken, a quintessential Mick on the Make, to use Roy Foster's terminology. He left Tipperary at the age of 14, moved to Australia and seems to have spent the rest of his life lying about everything. Less important than the many who disliked and mistrusted him was the small number of influential people - notably, Winston Churchill - who liked him immensely. He ended up a cabinet minister, chairman of the Financial Times and all-round political fixer and charmer, despite an appearance that combined a "mop of read hair and pale freckled skin" with "black teeth". He reaped the usual rewards, including a viscountcy. He downplayed his connections to his father, a monumental sculptor and founder of the Gaelic Athletic Association, as well as all things Irish, although he once produced his birth certificate to refute the claim that he was a Polish jew: in the British society that he embraced there were, after all, some things worse than being Irish. From the non-Welsh Welsh to the non-English English: this identity thing is very complicated.

I was thinking about this while reflecting on how people became Irish. The DIB, as we've already seen, is full of various arrivistes. This isn't surprising: Ireland is a small place, close to lots of big places, and you'd expect there to be lots of race-mixing to and fro. In fact, despite continuing self-identity as a highly homogeneous people, the Irish are as mongrelized as any: in my own family tree, other than the Hungarians on my father's side (and leaving aside the Greek gods of which I've previously spoken), I'm aware of Huguenot and Scottish heritage diluting my pure Paddytude, and there are probably other, unknown, miscegenating strains. This is fine by me and completely typical. But at the same time, reading Irish lives makes you very aware of those who elbowed their way in, particularly since so many make the kind of impact that gets them an entry in a dictionary of biography.

That's Richard Boyle in the picture: the first earl of Cork, who moved from England to Ireland in 1588, when he was about 22. He got himself a really great job: deputy escheator. Escheat is a feudal concept that still exists in common-law jurisdictions: essentially, it means that if the owner of title to land or other property cannot be found, that land or property "escheats" to the feudal lord, or these days to the state. In late 16th century Ireland, there was a lot of escheating going on, as the English crown looked for reasons to confiscate land from the established Ireland. Boyle was very good at this, and found all sorts of reasons to take land away from people who mistakenly believed they owned it. But once confiscated, he then skimmed, building himself a considerable fortune on the side. He then married another fortune, covering up the fact that his wife's late husband had committed suicide, which was another grounds for escheatment to the crown. His wife then obligingly died, leaving him owner of everything. Not unsurprisingly, these activities annoyed people. It was claimed that some Irish rebels took up arms against the English crown because of Boyle's corrupt activities and accordingly he was charged, convicted and jailed. But by this time he had friends in high places: he was released, pardoned, given a new job, fixed up with a second wealthy wife and a deal to buy Sir Walter Raleigh's estates in Cork for a knockdown price - Raleigh apparently needed the money because he was in prison at the time. (We've come across the Raleigh estate once before: the artist Edith Blake lived in his house near Youghal.) Boyle set about building up his fortune again, breaking Raleigh's leases, either to squeeze more money from the tenants or to put in new ones, usually English soldiers and entrepreneurs keen to loot Munster's rich natural resources. Boyle used the money to buy even more estates in Ireland and England; he also obtained the usual titles to go with his wealth and influence - first a knighthood, then a barony and finally an earldom. Hie second wife obliged him with 15 children of which at least 11 seem to have survived to adulthood. Boyle was energetic in obtaining them wealth and preferment, too, building estates and seeking out advantageous marriages. He lived to the age of 74 and died of natural causes. His family motto was "God's providence is my inheritance." I'm not sure what God had to do with it: the substantial inheritance of his family depended in great part on Boyle's dark genius for business, including a filing system that could keep him up to date on his tenants and their payments "at a moment's notice."

His third son, Roger, was similarly gifted. (The heir, also Richard, merely held on during the political upheavals of his lifetime, adding a second earldom and a viscountcy to his tally of titles.) Roger managed to navigate the turbulent politics of early 17th century Ireland with sinewy talent, switching from monarchy to Commonwealth to restored monarchy with great success. His father obtained for him the title Baron Broghill. The elevation to the earldom of Orrery was all his own work: he married the daughter of the earl of Suffolk and rose and rose and rose. Like his father, some of his wealth was obtained corruptly, although maybe not enough: the cost of his lavish lifestyle consistently exceeded his income. His friends praised his "devising head and towering wit". To these virtues the DIB adds "vanity and deviousness". He played the anti-catholic card whenever he had a chance.

The really talented Boyle was the first Richard's 14th child, Robert, who was born in Cork and became one of the outstanding natural philosophers of an outstanding era. He is the Boyle of Boyle's Law - the one about the proportional relationship between the pressure and volume of a gas - who worked tirelessly in experimental science, particularly chemistry and physics, while also seeking to lead an demanding religious life. Michael Hunter of the DIB nicely links the two strands, stating that "his laboratory practice can in many ways be seen as an extension of his indefatigable examination of his conscience."

The professional descriptions of the DIB continue to be illuminating: thus, you have to read the life of Samuel Boyse, once he's presented as "poet, translator and hack writer", and it's well worth it to discover the life of one whose "destitutions and extravagance were considered infamous even by the standards of eighteenth-century literary bohemia. (He once pawned his clothes and his bed linen and sat in bed writing, wrapped in a blanket.) Similarly, it's irresistible to learn about Reginald Brabazon (pictured) once he's been situated as "landowner, philanthropist and disciplinarian." He founded something called the Duty and Discipline Movement (as well as the Lads' Drill Association), whose aims, according to the DIB, were "to combat softness, slackness, indifference, and indiscipline in young people and to give reasonable support to all legitimate authority." Irresistible or not, I think that reading about him is probably preferable to having been in his company.

Finally, Brendan Bracken, a quintessential Mick on the Make, to use Roy Foster's terminology. He left Tipperary at the age of 14, moved to Australia and seems to have spent the rest of his life lying about everything. Less important than the many who disliked and mistrusted him was the small number of influential people - notably, Winston Churchill - who liked him immensely. He ended up a cabinet minister, chairman of the Financial Times and all-round political fixer and charmer, despite an appearance that combined a "mop of read hair and pale freckled skin" with "black teeth". He reaped the usual rewards, including a viscountcy. He downplayed his connections to his father, a monumental sculptor and founder of the Gaelic Athletic Association, as well as all things Irish, although he once produced his birth certificate to refute the claim that he was a Polish jew: in the British society that he embraced there were, after all, some things worse than being Irish. From the non-Welsh Welsh to the non-English English: this identity thing is very complicated.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

The first Boycott, the Belfast charioteer, a scarcely-known composer and little-known writer

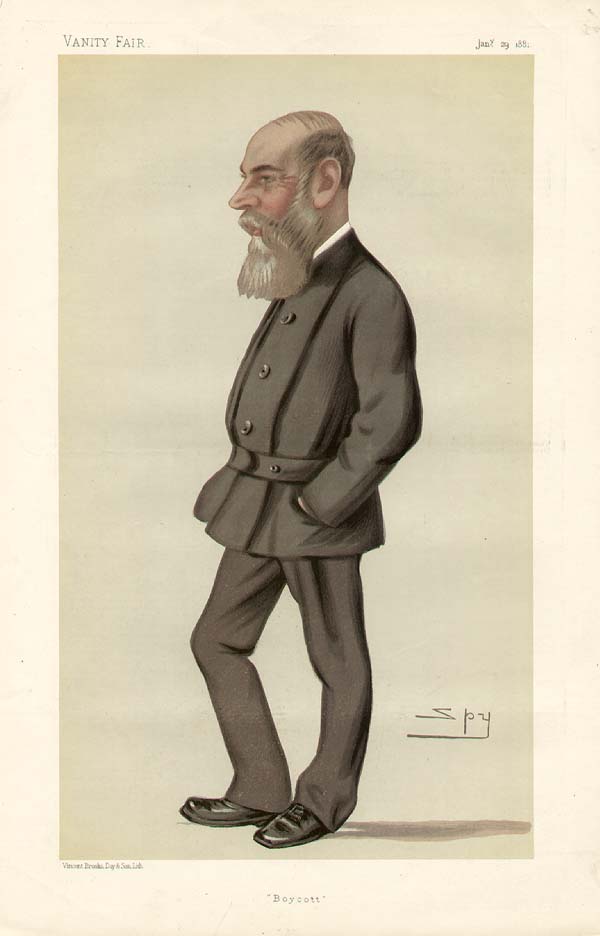

I have a distant memory of the 1947 film Captain Boycott, one of many black and white features that used to be staples of television viewing in the days before color television. Principally, I recall the great Scottish actor Alastair Sim playing an Irish priest Father McKeough - based on the real life Father John O'Malley - who led the popular ostracism in 1880s Co. Mayo of Charles Cunningham Boycott, an English land agent who while no "brutal tyrant" according to the DIB, believed that "the Irish peasantry were prone to idleness and required firm handling." In gratitude, said Irish peasantry meted out some firm handling of their own, partly inspired by the Irish political leader Charles Stewart Parnell, who had advocated the ostracism policy. (In the film, Parnell is played by Robert Donat, which at least is an improvement on the Hollywood biopic in which the great man was incarnated by Clark Gable, with Myrna Loy as Kitty O'Shea.) I do recall Sim getting the stirring closing speech, in which he describes what will be done to all others in the future who attempt to do what Boycott had done: "We shall boycott him!" It turns out that Father O'Malley actually did come up with the idea of turning the surname into a verb, helped by a journalist pal who popularized the term. The real Boycott's case became a cause célebre: the government brought in blacklegs to harvest crops at a cost of 30 times their actual value. Boycott, completely intransigent, believed the cure to Ireland's agrarian problems was emigration and industrialization. Happily for him, he got a job back in England, although he used to return to Ireland to holiday and, who knows, to gloat.

Stephen Boyd. Hollywood turns up so many one-hit wonders, and this Belfast man (Glengormley, near Belfast, as it happens) was one of them. But his one hit was a considerable one, Ben Hur, where he played the charioteer Messala to Charlton Heston's eponymous hero and became a huge, if somewhat short-lived star. He started out in amateur dramatics, and the DIB suggests that his pre-Hollywood career was somewhat perfunctory: in fact, he appeared in nine films in three years, including opposite Brigitte Bardot in Roger Vadim's 1958 melodrama Les Bijoutiers du clair de lune (The Night Heaven Fell). Post-Hur, the DIB records mainly his disappointment with his roles, without mentioning that he nonetheless appeared in films by John Huston, Edward Dmytryk, Richard Fleischer, Anthony Mann, Jean Dellanoy and Romain Gary. (I'm beginning to think the DIB isn't completely sure footed when it comes to film and television.) He dropped dead on the golf course at the age of 49.

I found the tiniest fugitive clip of the music of Ina Boyle, taken from a 1948 live recording with authentic coughing in the background. She was from Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow, not far from where my mother grew up and my father now lives. She studied under Ralph Vaughan Williams, who counted her as a favorite student, and composed widely, including an opera, three ballets, orchestral, chamber and choral works. She spent five years setting an Edith Sitwell poem to music, only for the poetess to refuse to let her have the rights. Much work went unperformed and unrecognized. Once, she grew peas to pay the bills. I couldn't find any of her music currently recorded, which makes the short, haunting clip even more precious. I'd like to hear more.

I wasn't familiar with the writer Patrick Boyle, but the DIB entry sent me to a short story of his in the Field Guide Anthology of Irish Writing. The story, Myko, is a nice little dark account of a publican's attempt to defraud a tinker over the sale of a coffin, and has a good sting in its tale, Roald Dahl-style. Boyle was a bank employee (he declined to follow his family into the law because of his stammer) "who struggled to write in between working and drinking." In 1965, he sent in 14 short stories to an Irish Times literary competition and took the first 5 places. The DIB says his "reputation receded somewhat in later years", but based on Myko, he's certainly worth a read, and I shall seek him out.

Stephen Boyd. Hollywood turns up so many one-hit wonders, and this Belfast man (Glengormley, near Belfast, as it happens) was one of them. But his one hit was a considerable one, Ben Hur, where he played the charioteer Messala to Charlton Heston's eponymous hero and became a huge, if somewhat short-lived star. He started out in amateur dramatics, and the DIB suggests that his pre-Hollywood career was somewhat perfunctory: in fact, he appeared in nine films in three years, including opposite Brigitte Bardot in Roger Vadim's 1958 melodrama Les Bijoutiers du clair de lune (The Night Heaven Fell). Post-Hur, the DIB records mainly his disappointment with his roles, without mentioning that he nonetheless appeared in films by John Huston, Edward Dmytryk, Richard Fleischer, Anthony Mann, Jean Dellanoy and Romain Gary. (I'm beginning to think the DIB isn't completely sure footed when it comes to film and television.) He dropped dead on the golf course at the age of 49.

I found the tiniest fugitive clip of the music of Ina Boyle, taken from a 1948 live recording with authentic coughing in the background. She was from Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow, not far from where my mother grew up and my father now lives. She studied under Ralph Vaughan Williams, who counted her as a favorite student, and composed widely, including an opera, three ballets, orchestral, chamber and choral works. She spent five years setting an Edith Sitwell poem to music, only for the poetess to refuse to let her have the rights. Much work went unperformed and unrecognized. Once, she grew peas to pay the bills. I couldn't find any of her music currently recorded, which makes the short, haunting clip even more precious. I'd like to hear more.