Son of Dracula (1943) is the one where Lon Chaney plays the cunningly-named Alucard, who travels to America. Obviously, nobody was going to work out his true identity from such a sophisticated word-jumble. So, equally clearly, none of you will be able to identify the true location of Lirenda, or its antagonist neighbor Angolea, as depicted in Henry Burkhead's 1646 play A tragedy of Cola's furie, or Lirenda's miserie. In a past life, to which I've previously referred, I spent quite a lot of time in the Bodleian library in Oxford, among whose advantages were holdings comprising virtually every book ever published in English. In my efforts to find something new to say about very well-mined material in 16th and 17th century drama I read some very obscure plays, which would arrive at my desk, dust-encrusted, inspiring science fiction fantasies about 400 year-old plagues preserved in the Bodleian stacks whose spores would be unleashed, fatally, on unsuspecting researchers. Unfortunately, most of these plays did not provide even that distraction: it turned out that they had been rightly consigned to the dust all those years ago, and did not really merit the temporary disinterment that I arranged for them. I suspect that Cola's furie is in that category, although I never got to read it at the time, it having been published six years after the unyielding cut off date for my studies. We don't know much about Henry Burkhead: the DIB thinks he may have been English. But he was somehow connected to the confederation of Kilkenny, which, as I mentioned yesterday, I'm not much interested in writing about. (Two days in a row: how much more uninterested can I be?) In it, the "catholic gentry of Lirenda ... defend their rights against brutal, treacherous Angoleans". That at least, seems to be an illustration of recognizable emotions, similar to those on display in my local pub the other week when Ireland thrashed England at rugby. That Lirendan-Angolean thing is always a rich vein to tap.

Denis Parsons Burkitt was a remarkable scientist. He came from Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, and after studying medicine at Trinity College Dublin he ended up in Africa - he had a parallel interest in missionary work - where he wrote papers on epidemiology and pioneered inexpensive prostheses for amputees. His first major work was on cancer: he first described a form of the disease in African children that came to be known as Burkitt's lymphoma, and his 1958 paper on the subject became a "citation classic", which I understand is a term of art for a widely-cited scientific work. He took a 10,000-mile safari through Africa to identify the coincidence of lymphoma and malaria, which resulted in the first connection between a cancer and a virus. Still working in the challenging conditions of Africa, he also pioneered the use of chemotherapy to treat lymphoma: the DIB says that Burkitt's "work is considered to be one of the most significant contributions to cancer research in the twentieth century."

Upon his return from Africa, he make a second major discovery: the correlation between the lack of dietary fibre and the incidence of colon and rectal cancer: his 1971 paper on the subject is another citation classic. This discovery is cited as the cause of a fundamental change in western diets. He was serious about his christianity and of his own work, he quoted the apostle Paul: "what do you possess that was not given to you? If then you received it as a gift, why take all the credit to yourself"?

It's a bit difficult to keep up with the names of Elizabeth Burnaby. Born Elizabeth Alicia Hawkins-Whitshed, she successively married Gustavus Burnaby, John Frederick Main and Francis Bernard Aubrey Le Blond, taking her husbands' names as appropriate. Since she published photographs, this means her works are listed variously as those of Mrs. Burnaby, Mrs. Main, and Mrs. Le Blond, which can make them difficult to track down. I found a copy of her book High Life and Towers of Silence, in which she's separately described as Mrs Fred. Burnaby and Elizabeth Main. But it's worth persevering because she was truly a remarkable woman, a pioneer of both mountain climbing and photography. She went to the Alps to improve her health, and they clearly had a good effect: she climbed Montblanc and the Matterhorn and many others during a 20-year alpine career, for obvious practical reasons in short skirts. She brought a camera with her from the beginning - first a cumbersome wooden affair with bellows and a tripod, later a smaller roll film camera - and took thousands of photographs, many of which were widely sold and appeared in books: in addition to High Life, she authored Hints on Snow Photography and contributed the photos to E.F. Benson's Winter Sports in Switzerland. (Follow the link to High Life to see some of her pictures.) She was from Greystones in Co. Wicklow, a lovely seaside village, now somewhat suburbanized but still attractive, which I've visited all my life and where my father now lives. The name of her first husband, Burnaby, is prominent in the area: his family had substantial estates there.

Mary and Lizzie Burns, were also impressive women. (Lizzie is in the picture.) Their father emigrated from Ireland to Manchester, and Mary worked as a teenager in the mill owned by the family of the socialist Friedrich Engels. They met in 1842, and she introduced him to the condition of the working class in England - which presumably had some influence on his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1844, which the DIB does not mention. They cohabited without marrying, which somewhat comically earned the disapproval of Karl Marx and his wife Jenny. She took Engels to Ireland in 1856, and he wrote an interesting letter to Marx about their trip. She died suddenly in 1863, around the age of 40: when Engels told Marx, he offered passing sympathy while complaining how short of money he was. Engels then became involved with Lizzie, who had already been living in his and Mary's household. The Marxes seem to have been warmer to her: Eleanor, Karl's daughter, became wedded to Irish nationalism thanks to Lizzie, and they both accompanied Engels on his second visit to Ireland in 1869. They enjoyed themselves, but Engels lamented that the Irish peasant was turning bourgeois. As Lizzie's health began to fail, they moved around England, Scotland and Germany in the hope of her recuperation. The day before her death in 1878, Engels and Lizzie married: she was buried in a catholic cemetery in London: I hope she hadn't turned bourgeois as well.

I'm curious as to why Napoléon Bonaparte was attended by five Irish doctors during his final days in Saint Helena. One of them, Francis Burton, from Tuam, Co. Galway, observed his post mortem and made the mould from which the emperor's death mask was struck - although there was an undignified quarrel over this when a Corsican doctor claimed credit. Burton's nephew was the fascinating and notorious explorer and orientalist Richard Burton.

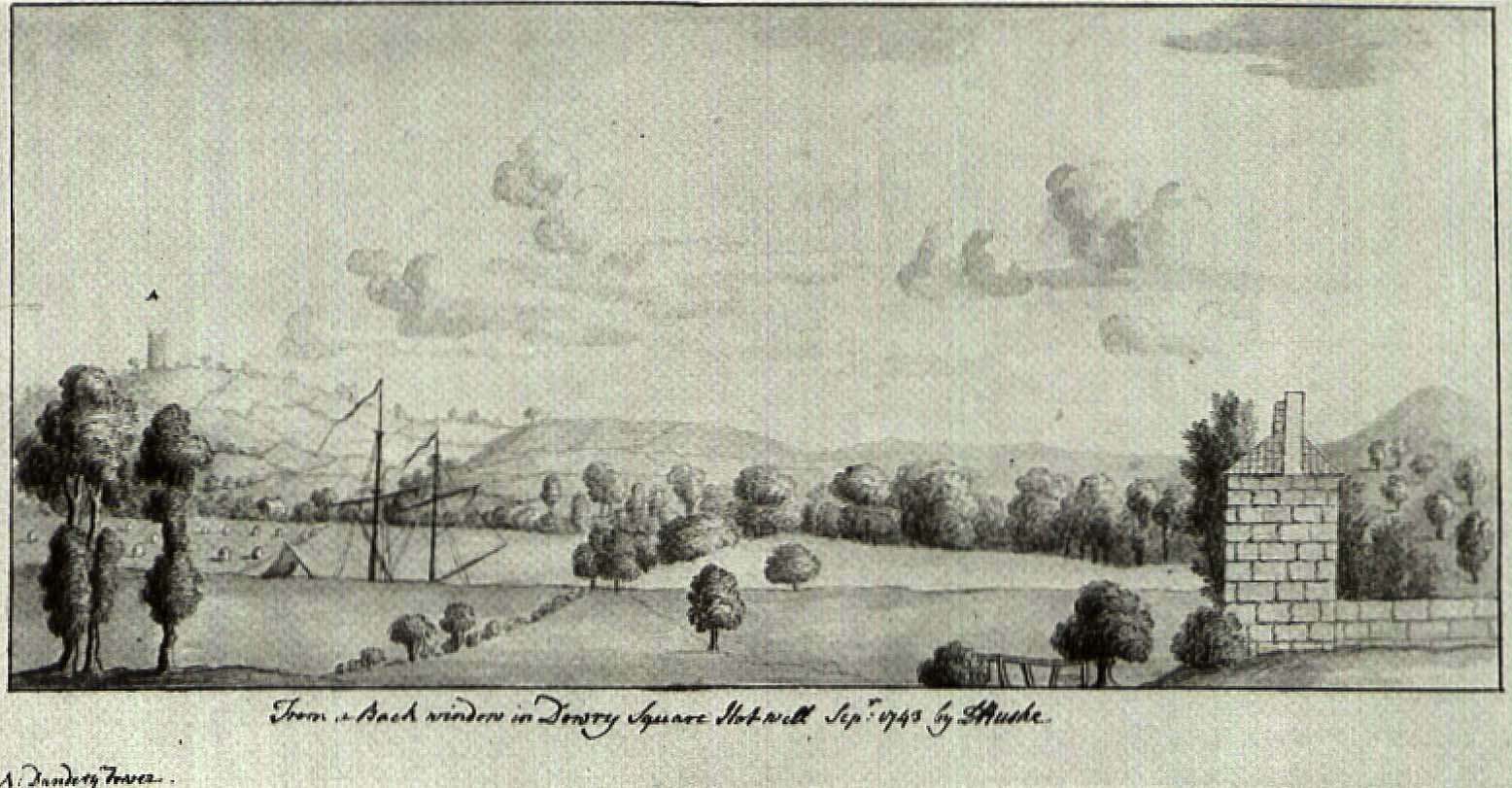

This picture probably does not do justice to the work of the artist Letitia Bushe, a Kilkenny watercolorist and miniaturist. Trinity College Dublin has archived some paintings, but these 18th century public domain works have been locked behind a password-protected wall to which a copyright notice has been attached! For shame ... She was a teacher of many artists, a great conversationalist and a beauty, who was saddened the loss of her former admirers after her looks were ravaged by smallpox.

Eddie Butcher came from a musical family: his father sang, as did nearly all of his siblings. He stayed close to his home in Magilligan, Co. Londonderry, where he worked as a farm laborer and road worker and sang, but never professionally. He had a huge repertoire of folk songs, and fortunately the collector Hugh Shields found him and recorded more than 200 works. He made many more recordings and broadcasts and was greatly appreciated by the 1960s generation of Irish folk singers. I found a recording of a wonderful unaccompanied song, Another Man's Wedding, here. (Legal streaming: do you have a problem with that, Trinity College Dublin?)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment